If you’re a design leader, you can’t make assumptions and expect to reach your goals.

When we have a Purpose and set goals for ourselves (like hiking to the top of a mountain), we identify our objective (the Peak), then determine the best way (the Path) to reach that goal and how we’ll carry out that Plan (the tactics).

Every UX strategy needs a solid framework to get started and stay on track. Sticking with the metaphor of a climb, let’s look at the 5 core elements of strategic frameworks.

1. Purpose – Why am I climbing this thing in the first place?

Is the goal clearly stated and understood? Has it been validated as something worthwhile to pursue? For whom? Does the team working toward this goal understand its purpose?

2. Peak – Choose your destination—or at least aim in a general direction. You may sometimes hear of companies focusing on their “North.”

3. Path – How you get to the peak matters.

How you climb the mountain matters. The path needs to help the organization not just meet financial targets, but also mature the organization in the process.

4. Point – Opportunity to pause, analyze, and measure.

Points on the path aren’t merely deliverables or activities. They should regularly confirm and/or adjust your goals and the path toward that goal.

5. Plan – Every expedition needs a plan for tactics.

I need the right training & equipment. I may need other people (Who should I bring versus station remotely?). Do I need to let others know where I’m going?

A lot of people mistake the Path for the Plan. True, each activity is a step toward the goal, but tactics are only one part of the strategy. The path is not a collection of tactics.

Constantly re-evaluate your framework to keep your strategy on track.

Table of Contents

Step 1: Purpose and Peak

Purpose ties into your vision of the intended outcome. It’s the first thing you define. I always start there.

Defining purpose means asking questions like:

- Why are we here?

- What value will we create?

- Who benefits from this value?

- Why will they care?

The Peak or vision (your intended outcome/destination) clarifies your purpose:

- Communicate the pain felt if the purpose is not achieved.

- Demonstrate one way the problem(s) get solved.

- Show how the problem’s solution adds value to users.

- Propose a realistic means of achieving the solution.

- Clarify any data that supports the purpose.

To make any peak truly valuable, it needs emotional and tangible merit. It can’t be expressed as a collection of features. Features only list the ingredients in your recipe – they don’t convey the whole experience.

Here’s an example from an initiative I led at Rackspace.

To define the purpose and peak, I dug into what “Managed Cloud” actually meant. I gathered a cross- functional group of people together for 2 days. First, we dove into “What is ‘managed’?” We deconstructed the term to identify the value for our customers.

I had to break through a lot of jargon bear traps—you know, the ones that leave you saying, “But that isn’t what ‘managed’ means. You’re making up random meanings.” Reflect people’s definitions back to them so that they gain a better understanding.

I then led the team through a storytelling exercise, where each person created a story with a customer (a Rackspace employee) and a scenario that reflected the new value. People didn’t simply tell fanciful stories. They explained what was wrong today and how we might improve that situation. By seeing the negative stories against a brighter future, our Purpose became more relevant and approachable.

We then captured that story in a shareable artifact that could discuss with other departments. In this case, we created a short photo essay with voice narration. A simple vision prototype.

We played the video in front of internal and external stakeholders and got a tremendous amount of positive feedback about what was working and what wasn’t. Once we connected user research to the points made in the video, buy-in soared. Product design, product management, and engineering all started prioritizing backlog items based on our new Purpose and Peak.

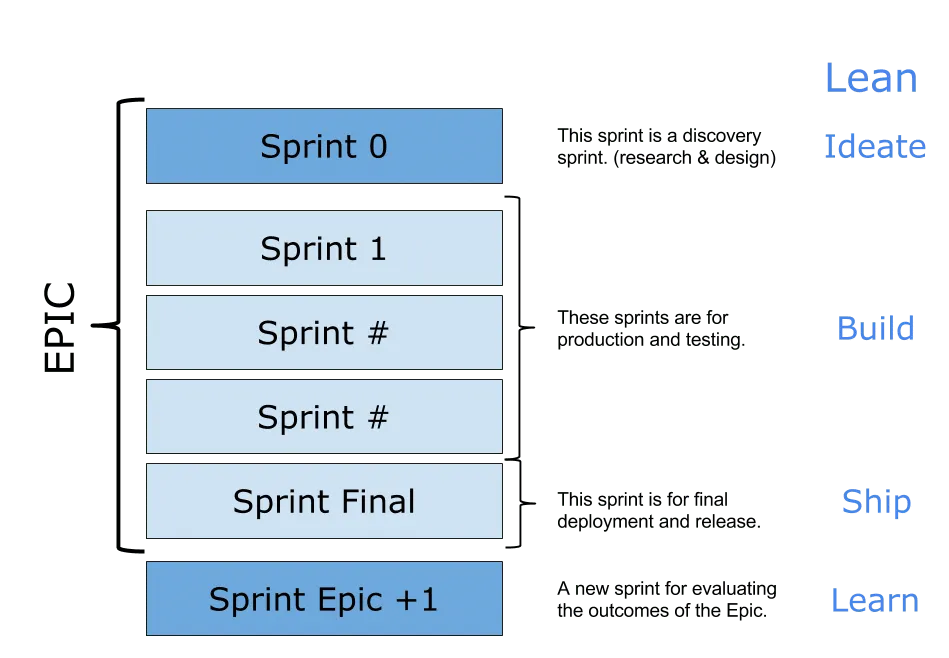

Step 2: Charting Your Path

The Path you choose to reach your destination isn’t the only feasible route. Each possibility requires weighing a variety of factors before adjusting course. Don’t decide your Path by thinking the “end justifies the means.”

Weighing the Options

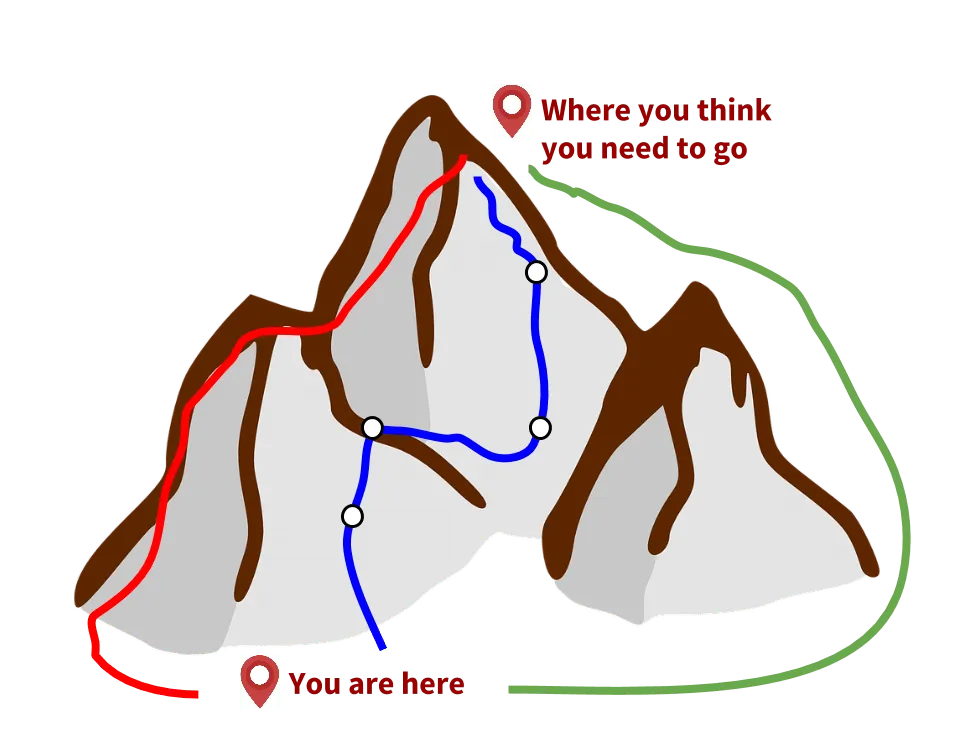

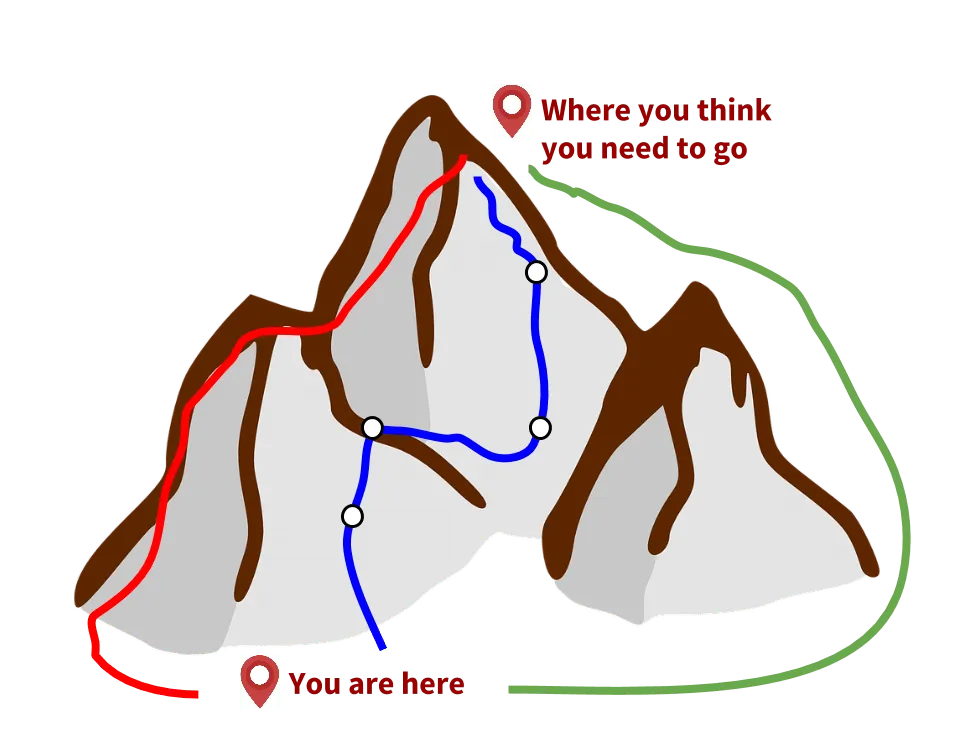

Let’s look at our mountain again:

Let’s say the red line has the following properties:

- Cheap.

- Fast.

- Quality (whatever that means to the organization).

Sounds like a good option. But is it? What if we throw in some factors that may or may not work for you?

- Requires reassigning key players from other projects (of lower priority, of course).

- Creates technical debt without a plan for paying it back.

- Doesn’t account for team development (to be ready for the next thing).

- The product releases on time, but lacks coordination with parallel sales & support efforts.

- Fewer points in the process to validate assumptions or apply lessons learned.

- No ability to instrument deliverables and offerings.

Does the red path still look appealing? What other options (and factors) can we consider?

If we go with the blue line, the path looks like this:

- A bit more expensive (short term).

- Takes longer to get to market—but more confidence that we deliver value.

- Results in better quality than we’d otherwise get—which leads to surpassing customer-based KPIs (like NPS changes).

- Provides definite answers to the bullet points associated with the red trail.

By taking the blue trail, you ship in a way that delivers the greatest value for both you and your customers.

Choosing the Right Path

How do you find the right path?

Know your organization’s culture, business, competition, capabilities, etc. Simple SWOT analysis helps, as well as the resourcing matrix explained in the previous chapter. Another tool I find tremendously useful is the“Culture Map,” as popularized by XPLANE. In this canvas, you uncover how the more intangible aspects of culture impact outcomes.

As you evaluate your options, consider the following criteria:

- How much technical and UX debt are we creating? Is it acceptable given our current state? How do we plan to pay it off?

- What other projects need to be deprioritized to accommodate our path? What will that cost the organization?

- How much time are we afforded to validate our assumptions periodically?

- Are we allowing enough time and leeway for non-design stakeholders to understand decisions (or weigh in with their own)?